Sydney: Riot and shanti shanti

From troubled to trendy: How Redfern, in the heart of ‘Eora Country‘, was controversially transformed from a poor, alcohol-drenched inner suburb into a haven for hipsters sipping soya-chai-lattes. Once synonymous with Sydney‘s indigenous population, Redfern has been colonised by latter-day Yogi’s and entrepreneurs. Times are indeed changing in the Australian metropolis.

There’s a mad dash on the platform, and the sound of announcements from the rusty loudspeakers merges with the telephones of the smartly-dressed commuters, who weave smoothly through the barriers and out into the streets.

Fred hands out one magazine after another. He’s returned to this patch practically every morning for years now, offering the latest edition of The Big Issue to the men and women who pass him by. Fred must be 70 at least. Deep grooves line his face, which tells its own story. He fondly recalls the days when he was kept company by another man, who would sit nearby playing on his didgeridoo.

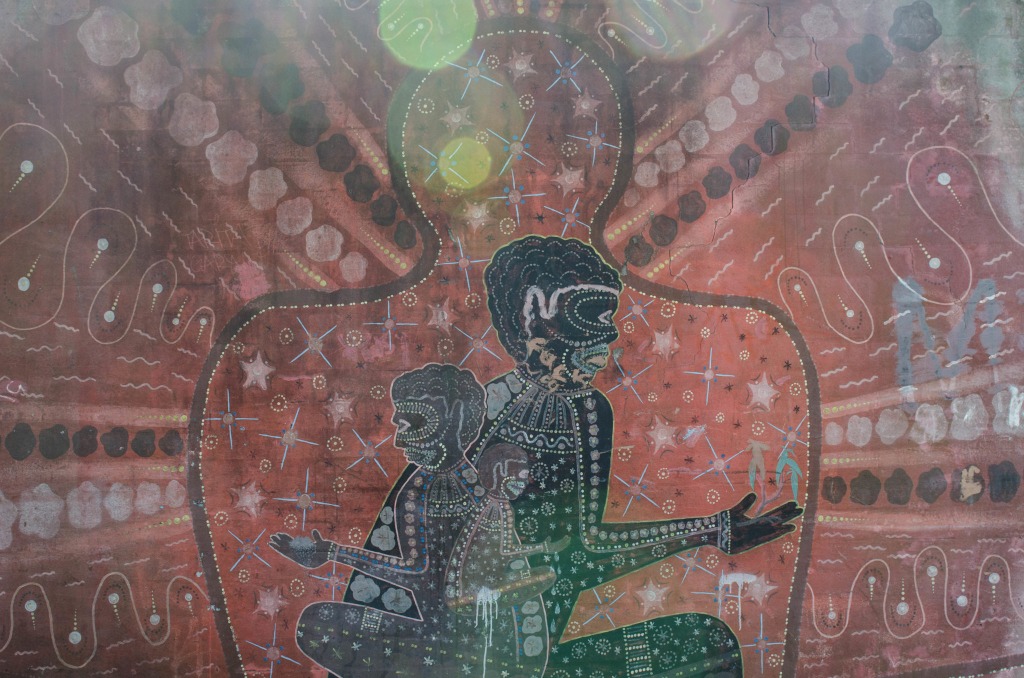

Redfern‘s murals tell its stories

At 9 o’clock in Sydney, Redfern Station is in the throes of its morning Rush Hour. Almost by the minute, trains arrive and depart from the city centre, the outer suburbs, and to the neighbouring Surry Hills and Alexandria. The steady stream of trains transports hundreds of workers, students and businesspeople to Sydney’s southern CBD.

This commuter bustle suggests little more than another ordinary working day. Yet there is something unsettling about the scene. The aboriginal murals on the walls around the station offer a distant echo of another time. These crumbling, fading surfaces allow a hint of once-bright scenes: of animals, people, landscapes and Dreamtime legends, as painted by the indigenous people who were Redfern’s original inhabitants.

Aboriginals settled in the area around Redfern many years ago, often referring to it as ‘Eora Country’ after the area’s indigenous owners. This name can still be seen around Redfern, painted in fading red paint on walls and laneways.

If you leave the train station and follow the brightly-painted murals on the walls, you will find yourself in the heart of the district. The streets have a quiet and calm vibe, it even feels rather hip. But this wasn’t always the case. Crime, protests, drugs, alcohol. Redfern was the scene of endless, awful daily battles. Plagued with unemployment and a lack of opportunities, Redfern’s aboriginal inhabitants found little peace here. Now that they are gone, little trace of them remains. The streets are empty. The plain, colonial-era terraces seem almost lonely and the playgrounds and gyms stand unoccupied. Barely anyone is here at all.

Riots in the indigenous idyll

Redfern represented, for many years, a thorn in the side of successive state and federal governments. Relocation schemes, large-scale building projects and systematic gentrification were among the sometimes cynical strategies employed to force out most of the area’s aboriginal residents. In 2004, their opposition to this process quickly escalated.

It was the closure of The Block, a collection of 21 houses on Eveleigh Street, not far from the train station, that signalled the beginning of the end. In 1973, this area – complete with social housing for hundreds of people – was granted to the aboriginals as a gift. Sadly, as time passed, the area became increasingly run down and rife with crime and drug dealing. For many Sydney-siders, Redfern developed a reputation as an unruly and dangerous ghetto. In 2004, a tragedy brought the situation to a head. A 17 year old aboriginal boy was killed while riding a bicycle during a police chase. The incident sparked the worst race-riots Australia had seen since the 60‘s. The closure and ultimate demolition of The Block followed.

Today, silence reigns on the empty plot where the aboriginal homes on The Block once stood. It is almost eerie. Yellowing advertising flyers have been stuffed into the overflowing letterboxes of long-abandoned buildings. The Block no longer exists. There is an immense mural, painted on a wall overlooking the plot, which serves as a solitary reminder of those that came before. It depicts the aboriginal flag: oversized and defiant.

The relentless Australian sun beats down, and the occasional gust blows a slight breeze across the unbuilt ground. When it does, it almost feels like a ghost, whispering tales from the dreamtime. An old pair of boxing gloves dangles from the iron grill in the window of Tony Mundine’s Boxing club & Gym, which only closed last year. With it, went two true veterans – Tony and the gym itself. Tony was a true fighter, and a man who stood up for aboriginal rights, both inside and outside the ring.

Redfern Sydney, a haven of soulless tranquillity and an emerging scene

No-one fights here anymore. The old lettering of the gym’s name on the brick building is barely legible now, the bars in front of the windows are rusting away and one can only imagine the hard and sweaty battles which once took place here.

Redfern has changed forever. It has become an altogether different place. A day spent in Redfern today feels like a stroll through the history of the Australian continent. You pass along the abandoned streets, alongside the storytelling murals and end up in the midst of what Redfern is now becoming: a centre of hip, contemporary culture, centred around cafes, art galleries and advertising agencies.

A short distance away from “The Block” chilled bass sounds are emanating from what appears to be a converted factory. There’s plenty going on in Henry Lee’s Café. The redbrick walls offer some shelter from the heat of the midday sun, metal bars allow a slight breeze to filter through and the sophisticated menu will hasten the heartbeats of vegetarians, vegans and clean-eating devotees alike. On the counter stand chic carafes of thirst-quenching water, garnished with cucumber, limes and mint. On each table, there is a bowl of sustainable brown sugar, and the staff speak French, Spanish and English.

Yoga, advertising and Redfern’s big future

Every now and then, attractive young women in yoga gear will pass through and disappear up a narrow spiral staircase to the Yoga-studio above. Everyone seems to be living in the day, just catching up with friends or doing a bit of work on the go.

Redfern has been utterly transformed. Less than a decade ago, even changing trains at Redfern station was considered slightly reckless. Today, it is a place in which advertising campaigns are created, galleries are opened and yoga sessions are held. So much has changed and in the process, a chapter from Australian history has been erased, whilst a new one is written.

During lunch hour, Henry Lee’s is doing a roaring trade, although the street outside is as empty as ever. One group of people you don’t see here: Aborigines. Neither in the mornings, nor in the yoga group, not even among the lunchtime throng. The vast majority have left their bittersweet homeland in Eora Country behind, with many travelling to south western NSW. Just one figure from the past remains: Fred, the non-aboriginal. He stands outside Redfern Station, which is now busy in a way that it never was during those years of crime and poverty. The emergence of modern cafés and restaurants with healthy fusion-dishes is of little interest to him. He is only here to sell the Big Issue, and he knows there will always be more, and bigger issues, to come.

No comments yet.

Be the first to comment on this post!